Multi-tasking doesn't work. Not for me and not for you. Not for women, not for men, and not for teenagers any more than their parents. Our brains make it so.

And yet we do it all the time, perfectly successfully.

How can both things be true?

How we multi-task successfully

I am successfully multi-tasking right now, and so are you. Here's what I'm doing, all at the same time:

Things directly related to the task (writing this piece)

Thinking what words to write

Typing them - which in itself is multi-tasking because I am both deciding what key to press and making my fingers press it

Focusing on the task rather than being distracted by something else

Thinking about what I’ve already said so that I can judge whether I’ve said it clearly enough yet and what else I need to say

Thinking about what I've already said so as not to keep repeating it

Thinking about what I've already said so as not to keep repeating it

And things not directly related to the task

Remaining upright rather than slumped - operating all the many muscles for this

More than that, I am actually walking because I work at a desk treadmill - and this helps me concentrate on the task, rather than hindering

Remaining aware of my physical body so that I don't do something inappropriate and offend (or amuse) anyone who happens to walk past my desk

Staying aware of the time

Drinking coffee

Most of the time, most of us can do certain things simultaneously without any loss of attainment. We can walk while chatting to a friend. We can eat while reading or watching a TV programme. We can listen to someone while doodling. We can even, in certain circumstances, work well while listening to music.

But these are combinations of tasks that are possible for very specific reasons and are very different from other combinations of tasks which are not possible. It’s important to distinguish between the two types of task and then you will see that the things we usually mean when we say “multi-tasking” are not possible together without an important loss of attainment on one or both/all.

The “things directly related to the task” are one task - the goal in my case being “to write this article”. So we can call that one thing. And the things not directly related to the task are all things which occupy very little brain bandwidth: I am doing them without paying attention to them. They are virtually or actually automatic. I do not have to think about them. So they are, to all intents and purposes, nothing.

So, my example above is not true multi-tasking because it is one thing (the task) plus virtually nothing. The small unrelated things are just not occupying sufficient brain bandwidth or attention to harm the main task. They don’t count.

If, however, I added in something such as checking my social media, answering a question from my husband, suddenly remembering to add something to a shopping list, or answering or writing an email, each of those things does require brain bandwidth so I have to divert attention from the main task, even if briefly. And there is a loss of attention on my core task.

This will have one of two (or possibly both of two) negative effects:

The task will take longer because I’ve lost a bit of time both switching away from it and switching back to it

I may - and in fact am likely to - perform less well on the task because of the loss of concentration.

You might think there could be a benefit as I might return to the task refreshed or with a new insight. This is only likely to happen if I was genuinely tired and struggling before I switched and if I did something refreshing during the switch. Writing an email (etc) is not refreshing.

WHY can our brain not multi-task effectively?

There are two main reasons. One is the “finite brain bandwidth” theory, which I’ve talked about before. (For example, here.) This basically says that brain bandwidth is finite, not stretchy, and if you try to fit more than one high occupier into your finite attention span, something has to suffer (and usually everything). Since writing/thinking and listening/reading are high occupiers, you cannot usefully listen to or read more than one thing at a time, or respond to a question while concentrating on something else. A neat illustration of this is the impossibility of having a phone conversation while someone else is asking or telling you something.

The other explanation is to do with how our brain pays attention, how it allocates the bandwidth.

Let me explain in words

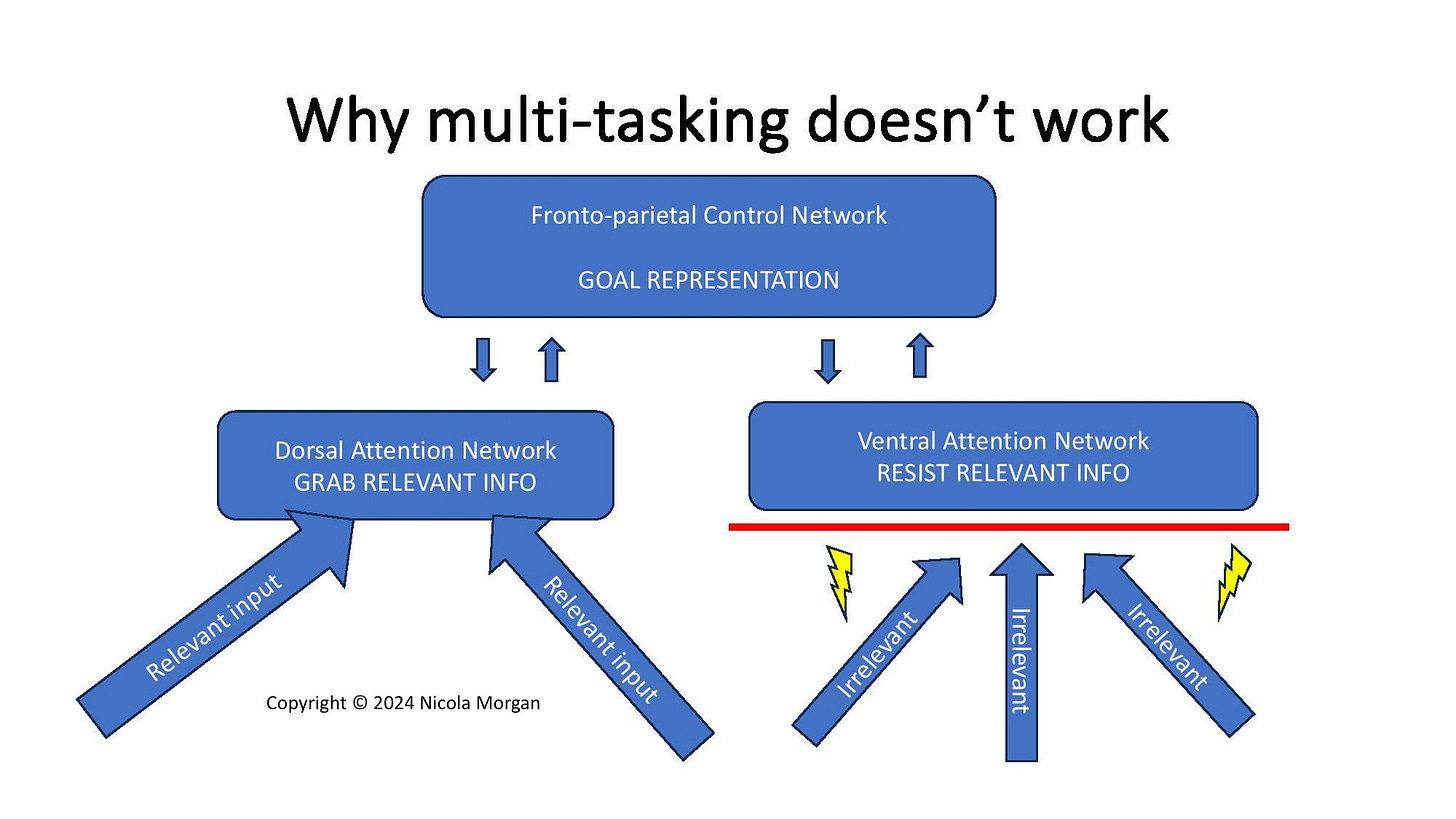

When you have a task - such as my task of writing this article - the Fronto-parietal Network (FCN) makes a representation of the goal, not an image (unless the goal is an image) but an understanding of what this goal is. The FCN asks the Dorsal Attention Network (DAN) and Ventral Attention Network (VAN) to gather relevant and block irrelevant information. And the FCN, DAN and VAN have to keep working to stay on task. Blocking irrelevant info is a huge one as our brains love to be distracted - because that distraction might be really important, such as something dangerous. (It usually isn’t dangerous, just tempting.)

(Note: the above image makes it seem as though the DAN and VAN have those precise and opposite tasks but that’s an over-simplification. I want to show that the VAN has more of a role in the irrelevant info.)

This action between the FCN and the Attention Networks is hugely brain bandwidth heavy. We just can’t do it for more than one big task at a time.

And when we try, our performance on the task suffers. That doesn’t matter if the core task is trivial, or perhaps even if it’s easy (because we’ll use less bandwidth) but it matters a lot of it’s a task that means a lot to us. Including writing this article.

As an important aside, it’s well established that even having a phone present, for example on our desk, occupies some bandwidth and reduces our performance on a task. For the references to this, see the research topics section of my website and scroll down to Life Online.

Conclusion and takeaway

We delude ourselves if we believe we can multitask without losing performance. We almost never can. If we’re honest, I don’t even think we need to be told this by scientists: we know. It doesn’t feel great and it doesn’t feel worthwhile. Our brain feels fractured because our brain bandwidth is being split and scattered. Shredded.

Unitask, don’t multitask! Put your phone/email/TV/family/temptations out of sight and out of hearing. Feel the intense flow of being fully engaged on task.

Photo credit: Ali Ford Photography

For more on this and the fascinating - or is this just me? - science of how our brains try to process all the info around us, and how to help our brains do the best job they can:

See my main website and put multi-tasking in the search box. I have just uploaded some new resources on this - see the blog post there dated Jan 22 2024.

Book me to speak to your school’s parents or staff, or any other adult audience. (I now rarely speak to young audiences as speaking to adults is a better way to spread my ideas. But I will do a Q&A with secondary school students.)

If you’re a member of the School Library Association, wait till June when I’m speaking on this topic at your annual summer course.

There’s an excellent piece of academic work available to all here: Multicosts of Multitasking by Kevin P. Madore, Ph.D., and Anthony D. Wagner, Ph.D. This was what influenced my second explanation above. There’s good stuff about task-switching, too.

Take a look at my book on the effects of our lives online - and how to live better with our distracting but wonderful devices: The Teenage Guide to Life Online is really for all ages!

Now I should get back to my other big task for today, writing some words of (or even thinking about/planning) my in-progress novel. That definitely occupies a lot of bandwidth!