Here, at last, is the final part of my musings from my recent trip to Sharjah and Dubai for the Sharjah Children’s Reading Festival.

For the previous parts:

Introduction - including thinking about thinking

Part One: Eating Porridge From a Stick - About surviving (and occasionally thriving) doing author events and all the travelling exhaustion - How the key is knowing what you need and preparing as much as possible to have that.

Part Two: Drinking Watermelon From a Goblet - about some wonderful experiences with schools and young people in the Middle East and musing about cultural differences (based on my not very massive though also not tiny experience)

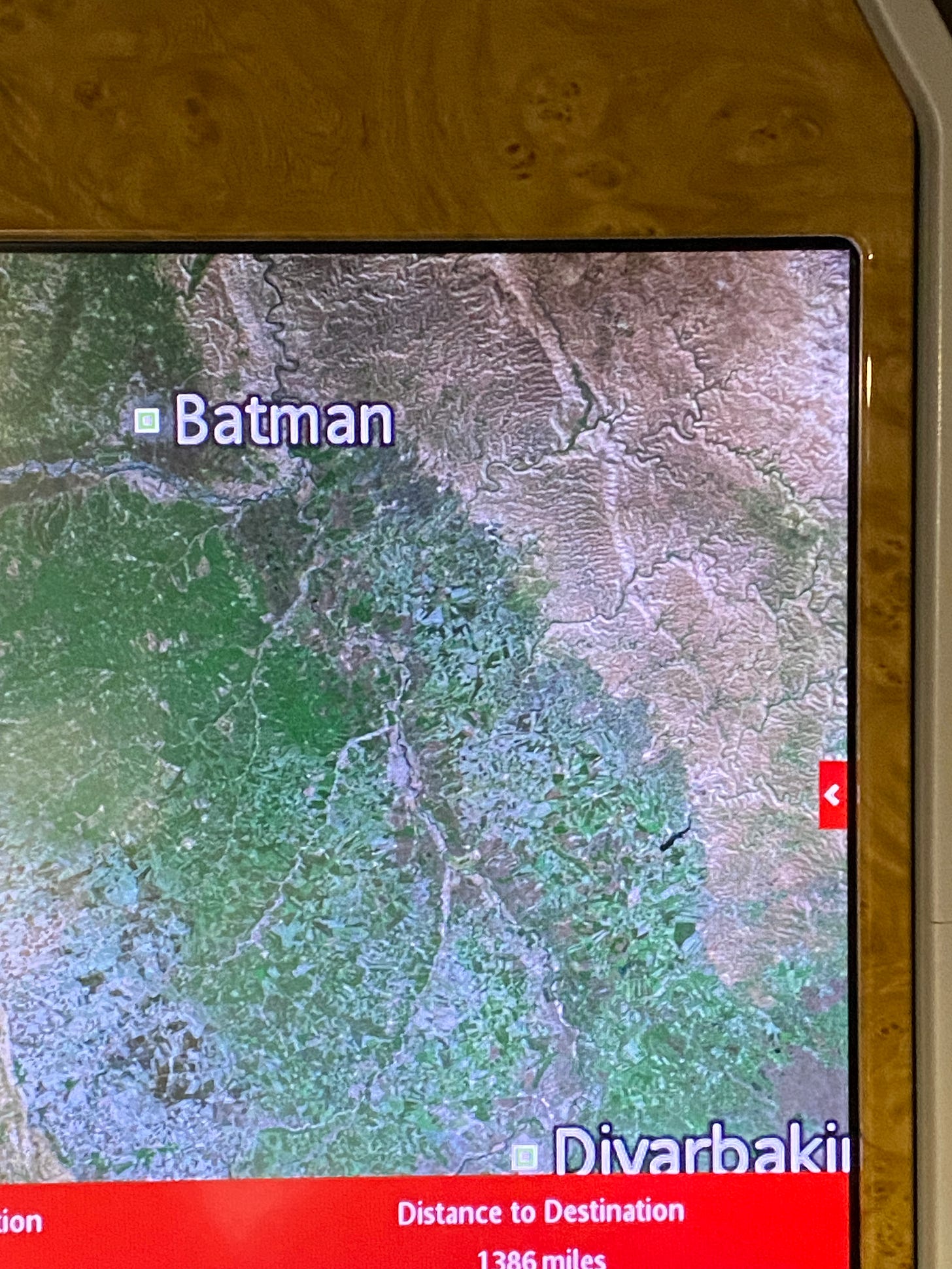

Meeting Batman in the Sky

My younger daughter, who has two small boys and almost no moments of peace, dreams of going on a long plane journey on her own so that she can watch back to back films without interruption. I, on the other hand, have literally never watched a film on any of the many long plane journeys I’ve been on. I have my screen set to the map that shows where we are and, when not reading a book, I am engrossed by thoughts of the countries beneath me.

I’m not sure whether I can put all this into words but I have to try. These are thoughts that have confused and exercised my brain on so many occasions when flying around the world. When I sit at home and read news stories from distant lands, of course I try to put myself in faraway shoes, to be empathetic and caring, to learn enough to have the right response, to wish, of course, that the world was safer and better in so many ways, to be grateful to those who are doing things to that end and to be grateful for my own safety. I am, on those occasions, very aware that my life is relatively safe and relatively lucky and that there are wars in many places where I don’t live. But then I finish reading the story and go back to whatever thing I need to do that day.

But when I fly over countries where lives are so much tougher than mine, I feel … I don’t quite know how I feel. There’s something about being “above” that makes me feel a dreadful privilege. For a start, I am flying in immense luxury. Business Class, especially in Emirates, provides crazy comfort and as much champagne as even I can drink, served by people who behave as though in a high-end restaurant. I am also relatively safe - though it’s not logical to feel safe in a metal and plastic tube 40,000 feet above solid ground.

I am above and looking down, passing over, not even slightly experiencing the countries I am crossing. I am using them to get where I’m going. Down there, in some places they are suffering, fighting wars, blowing each other up, or struggling to survive in heat or cold or lack of food.

I can’t honestly get my head around how and why I am flying with a glass of champagne in my hand over the Black Sea - isn’t that Crimea and Ukraine just to the North? - and a bit of Syria and Iraq and the edge of Iran. How can we be doing this, so safely, while below is far from safe? How is this reasonable, ethically, practically?

And then Batman appears on my screen and I smile and have to take a photo of it because it’s funny. But of course it’s not funny - it’s a real place, in Turkey (thanks, Google, which I can access from my privileged plane seat) with real people who do not need me laughing at the name of the place where they live.

What is my point?

I think we can learn something from this about how to live well and healthily in a world which is - and has always been - full of danger and full of injustice. Let me (try to) explain.

I have always taught that the secret to wellbeing, mental strength and generally coping with Life and whatever it throws at us, is to spend as much mental space and time as possible on things we can control and as little as possible on things we can’t. However, I think I can add something to that: it is also important sometimes to spend time thinking about Big Things, even if we can’t control them. After all, if we didn’t, we might miss something we could do to help other people or ourselves.

You see, it’s all too easy to be complacent and refuse to think about awful things in the world, on the grounds that we can’t do anything about them. That would be a healthy defence mechanism. But if we all did that all of the time, we would be “alright, Jack”, but we would not have made the world even a tiny bit better. And if we don’t make the world even a tiny bit better, what does that make us? Happy? Really? Mentally strong? Really?

Here is my revised advice

First, yes, we must look after our own minds. To do that we must not get tangled up in fretting about things (and people) that we can do nothing about. yes, we should spend mental space mostly on what we can control or change.

Second, however, we must spend some time thinking about things (and people) that we think we can’t do anything about, just in case we can.

We have more power than we think. We can help. We just have to decide how much we can afford. It might be time, or money, or support, or campaigning. It might be helping in a charity shop or donating some money to the charity. It might be writing a letter. It might be not buying from a company that behaves badly or a product that damages the environment. It might be so very many things, small or big.

THIS is what I want to say, to alter the advice I’ve often previously given and to say as well:

Second, however, we must spend some time thinking about things (and people) that we think we can’t do anything about, just in case we can.

So my rambling thoughts as I “looked down on” those countries as a flew over them were not wasted. The balance we each need to achieve, as we grow up and become wiser, is between first not expecting ourselves to do more than we can and, second, asking ourselves what we can do. Putting ourselves first, just as we have to put our own oxygen mask on before helping others, but then seeing in what way we can help others. Thereby making the world just a tiny bit better, without making ourselves any worse.

On that note, I commend to you the Substack of a friend of mine whose actions I cannot even begin to imagine emulating:

My own actions are much smaller and do not put me in any physical danger. Most of the time I find looking after myself and my family is the most I can manage! But I’m not going to beat myself up. I do what I can when I can and occasionally take time - not necessarily 40,000feet up - to think about whether I can do more.

Although I didn’t plan this, because I’m not a planner, that thought takes me right back to the first in this series, when I talked about the importance of making time for thinking.

Here ends my rambling Thoughts From an Author Abroad!

I wish you some thinking time, whatever you want to think about.

Thank you very much for the recommendation! This was a nice surprise. And yes, I definitely agree with this post. After two years coming and going from Ukraine I think my top single piece of advice to people who think they ‘can’t do anything’ is to donate… *intelligently*. Almost everyone in the West is in a position to donate some money to charity, but if you want more than a sop to your conscience, identify a charity with provable achievements in the area you care about. Not just the ability to do a photoshoot and pay £££s for ads claiming that five pounds could feed a child for a week – yes, it could, but verify that this is what the charity will use it for. When it comes to donating to international aid work in particular, an hour’s deep dive googling could be the difference between your money getting into the hands of on-the-ground staff who will use it to help people or sitting in the bank account of an org that doesn’t even send people to the affected area because it’s considered too dangerous to visit.

A shift in behaviour arising from this awareness is probably the single biggest thing we as individuals with no influence over state and major corporate actors could do. (My personal recommendation to anyone who isn't confident finding a genuinely local organisation is World Central Kitchen, because I and other volunteers have personally seen their vans all over east Ukraine, and hopefully that applies in other conflict zones too.)